Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

Vintage flag unlocks story of fallen soldier

Discovery linked to Soudan man who died in WW I

TOWER- For years, Clair Helmberger, of Tower, has hunted treasure of various kinds, so when the contents of an old garage in Tower were offered for sale this past spring, the hunt for treasure was …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

Vintage flag unlocks story of fallen soldier

Discovery linked to Soudan man who died in WW I

TOWER- For years, Clair Helmberger, of Tower, has hunted treasure of various kinds, so when the contents of an old garage in Tower were offered for sale this past spring, the hunt for treasure was afoot again.

And this time, there was indeed treasure to be found, historical treasures 100 years old and more, including an oversized 48-star American flag that once draped the coffin of the first area soldier to be killed in battle in World War I.

The garage had once belonged to lifelong Tower-Soudan resident Rick Nelson, a U.S. Army veteran who died in a Virginia care center in June 2021, at the age of 73.

The Tower Economic Development Authority had acquired Nelson’s former property in May 2020, and as part of ongoing efforts to clean it up for future use, the contents of the garage were offered for sale last spring. Helmberger’s offer of $250 was the only one received by TEDA, and they approved the sale in June.

Helmberger knew there was a lot of wood in the garage, but when she started looking around, it was an old suitcase tucked in a corner that caught her eye.

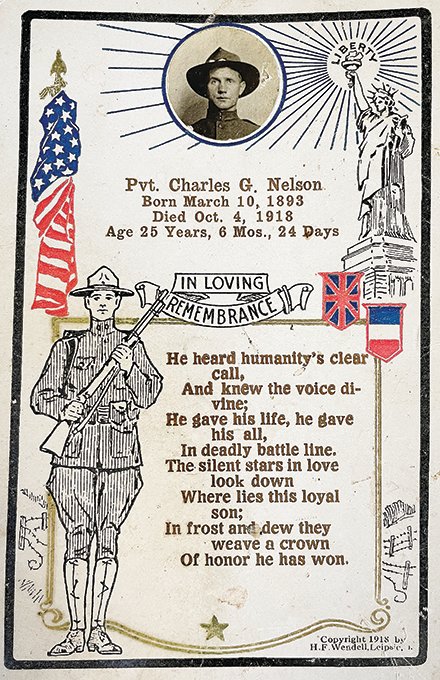

“I opened it up and found the flag and all these other things,” Helmberger said, things that included old photographs and albums, and two printed cards commemorating the death of World War I Army soldier and Soudan native Charles G. Nelson.

“I brought it home and started going through all the photos and kind of pieced it together,” Helmberger said.

Two large photos of a long procession along a town road provided a telling clue. The procession was led by a horse-drawn funeral caisson carrying a flag-draped casket. She shared her discoveries with her brother, Marshall Helmberger.

“I had known about that funeral procession,” he said. “When I saw that flag and put two and two together, I realized this was an important item.” He concluded that the flag had to be the one covering the casket of Pvt. Charles G. Nelson during his 1921 funeral procession.

Charles G. Nelson

Charles Gustaf Nelson, born in 1893, was the third eldest of ten children born to Gustaf and Mary Nelson of Soudan. Gustaf and Mary emigrated from Sweden to the United States, he in 1888, she in 1889, and they married that year.

A farmer at the turn of the century, by 1910, 50-year-old Gustaf was working in the Soudan iron mine, with his now 17-year-old son Charles working beside him. In 1914, the pair were surely aware of the onset of a “great war” in Europe, but as President Woodrow Wilson had declared America’s neutrality in the conflict, life continued much as it had.

That changed when Wilson declared war on Germany in April 1917. Charles, now 24 and still working at the mine, was among the first wave of thousands of Americans between 21 and 30 required to register on June 5 for a newly created draft. He wasn’t called up immediately, but his time was growing closer in February.1918 when he went to Duluth with numerous other conscripts from the region for military physicals.

Finally, on May 25, 1918, Nelson was sent to Camp Lewis, a new Army camp near Tacoma, Wash. ,capable of housing more than 40,000 soldiers, to train as a member of Company G, 364th Infantry, 91st “Wild West” Division, so named because most of its troops came from western states. Soldiers from Camp Lewis were routinely being pulled and reassigned to fill other units headed overseas. As a new arrival, Nelson was there only a few weeks before his company boarded a train in late June or early July for the six-day trip to Camp Merritt, N. J. to prepare to go overseas. Along the way they passed through town after town where well-wishers stood by the tracks waving flags and cheering support.

On July 12, Nelson and his unit left the military harbor in Hoboken, N.J., on the HMT Olympic, sister ship of the Titanic, which had been retrofitted and camouflaged for the war to carry up to 6,000 troops, two-and-a-half times more than its peacetime capacity. Charles Nelson was going to war, and it was the last time he would see American soil.

The trip to England typically took 12 days, owing to the need to chart a zig-zag course to avoid possible attacks by enemy submarines. After landing, the troops were transported by rail to ports on the English Channel for the final boat leg to France.

Like all units arriving in France, the 91st Division was supposed to receive three months of intensive training before engaging in battle, but after barely a month the division was pressed into duty as a reserve unit for the Saint- Mihiel offensive. Nelson, with barely two months of training total, was not needed in that battle, and instead would see his first action in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the largest and bloodiest military offensive in U.S. history.

Tucked into the northeast corner of France, the Meuse-Argonne region was a rough, hilly mix of thick forests, ravines, and farmland. The main rail supply line for German forces ran through the region, and the primary objective was to mortally wound the German war machine by cutting that line, hopefully bringing the war to a swift end.

Traveling only at night by truck and marching to avoid detection by the Germans, Nelson was among 600,000 U.S. troops that made their way to the “jump off” line for the battle, which was to begin Sept. 26. Again under darkness, Americans replaced French soldiers along the battle line, with Nelson’s untested division drawing one of the most daunting assignments. Deployed along the western front of the nine-division offensive, the 91st Division was to cut through three successive lines of German wire entanglements, machine-gun positions, and concrete fighting posts to outflank and help capture Montfaucon, a hilltop German stronghold that had withstood numerous previous French attacks. With any luck, the division was expected to cover only about four miles that first day.

As Nelson hunkered down on the night of Sept. 25, any notion of sleep was shattered by the thunderous roar of U.S. artillery shelling German positions, beginning shortly before midnight and increasing in intensity until 5:30 a.m., Sept. 26, when the troops were ordered to attack.

Thick fog made worse by the smoke of artillery fire limited visibility in places to only 50 feet throughout the morning as the troops advanced. Nelson’s infantry unit followed another into territory that was largely forested, with ravines and hills along the western edge. The Germans had focused their defenses more in open areas, not expecting the enemy to send a full complement of forces through the forest, so the 91st Division moved ahead more quickly than those on either side.

However, somewhere, sometime during that first day, Charles G. Nelson of Soudan became one of over 26,000 Americans who eventually died in the most decisive offensive of the war. Nelson was buried in an isolated grave in the vicinity of Vaquois, likely quite near where he was killed, as the forces relentlessly moved onward in an offensive that would last until the armistice ending hostilities went into effect on Nov. 11.

Gustaf and Mary Nelson did not learn of the fate of their son until Dec. 1, well after the country had been celebrating the end of the war, news which began a surely excruciating wait for his body to be returned home.

In May 1919, Nelson’s body was retrieved from its isolated grave and re-interred in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon. It would be two more years before the USS Wheaton funeral ship returned Nelson’s remains to the same New Jersey port he left from in August 1921.

His casket arrived home in Soudan on Sept. 16. A delegation from the Nelson-Jackson American Legion post, named for Nelson and Fred Jackson, a Tower soldier killed in November 1918 who was returned and buried earlier that summer, stood watch as Nelson lay in state at his parents’ home until his funeral on Sunday, Sept. 18. Services were held at the Swedish Baptist Church in Soudan, after which the long procession to Lakeview Cemetery, led by Nelson’s flag-draped coffin, began.

“The procession included practically every member of the Nelson-Jackson Post American Legion, in uniform, the Soudan Concert Band, the Red Cross, fraternal societies and others, who marched, a long line of automobiles bearing friends of the deceased bringing up the rear,” the Tower Weekly News reported.

Passing the flag

A plaque on Tower’s McKinley monument recognizes five area soldiers who lost their lives in the war. Two of those individuals, Anthony and Frank Znidersich, were Soudan natives who were killed in May and August 2018, but both had moved away years before the start of the war. They still were considered “Soudan boys” because they were raised there, and their stepmother still lived there in 1918. Fred Jackson’s name is there, and Hillard Aronson, the fifth soldier memorialized on the plaque, died of pneumonia in a hospital in England on Sept. 28, 1918, two days after Nelson.

So, Nelson was the first soldier living in the area at the time of his induction into the Army to die in the war, a fact that has long interested Tower-Soudan Historical Society curator Richard Hanson.

“I’ve been interested ever since I had photos that said he was the first person from here killed in the war,” Hanson said. “I didn’t realize he was related to Rick Nelson.”

Hanson was uncertain of the relationship, believing him to be perhaps a cousin, but additional research by the Timberjay discovered that Rick was actually Charles Nelson’s nephew. Rick’s father, Richard O. Nelson, was Charles’s youngest brother, only 10 years old when Charles was killed in 1918.

Hanson met up with Clair Helmberger at the Timberjay office last week to receive the flag and other memorabilia on behalf of the historical society.

“I didn’t know there was this much stuff,” Hanson said. “I didn’t expect to have this much. I thought it was a flag and a couple of pictures.”

Nelson said he plans to create an exhibit featuring the flag and Nelson at the historic Tower Fire Hall when renovations there are completed.

“This is becoming a bigger exhibit than I was thinking of,” Hanson said. “I see it as probably a permanent exhibit about World War I as it involved Tower, Soudan, and the surrounding area.”

Toward that end, Hanson would welcome hearing from others who may have photos, memorabilia, or records from the war years. He can be reached by calling 218-404-2810, or by email at rv.hanson42@gmail.com.

(Editor’s note: While Charles G. Nelson is recognized annually with other fallen service members on Memorial Day, his story would not have been told without the stewardship of Nelson’s memorabilia by Army veterans Richard O. and Richard A. “Rick” Nelson. The Timberjay hopes that this story, compiled from numerous historical sources, serves as a timely reminder of the sacrifice all veterans have been willing to make for their country as we celebrate Veterans Day this week.)