Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

The present is the past for the pandemic

A look back at the local parallels of an epidemic from a hundred years ago

TOWER- About halfway up the hill toward the west end of Lakeview Cemetery in Tower is a large, rough stone family marker, with the name “Campaigne” inscribed in a smoothed oval. Nearby, …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

The present is the past for the pandemic

A look back at the local parallels of an epidemic from a hundred years ago

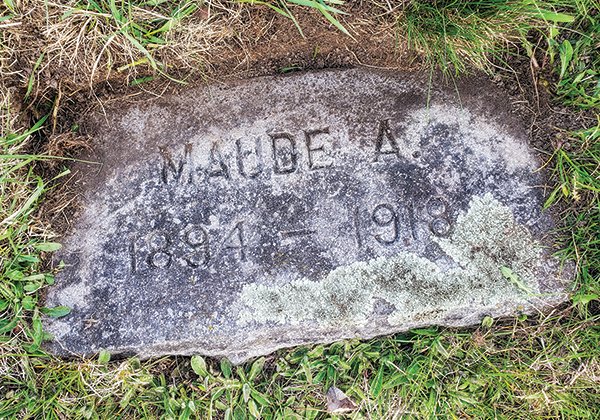

TOWER- About halfway up the hill toward the west end of Lakeview Cemetery in Tower is a large, rough stone family marker, with the name “Campaigne” inscribed in a smoothed oval. Nearby, severely tilted and partially covered with grass and dirt is a headstone, “Maude A. 1894-1918.”

1918 was a tumultuous year for Minnesota. Many young men from this area had answered the call of the nation and were engaged on the battlefields of Europe in the “great war” we know today as World War I. Much closer to home, the first two weeks of October were scarred by massive fires that started near Cloquet and Moose Lake, blazes that destroyed 38 communities, scorched 1,500 square miles, displaced 52,000 people, and claimed the lives of more than 450 others.

However, Maude Campaigne was a casualty of a third great tribulation, the Spanish influenza epidemic.

Some historians believe the worldwide epidemic had its roots in the United States, with the first case identified at Fort Riley, Kansas in March and taken throughout the country and abroad by thousands of U.S. soldiers. Other theories point to France, China, or Great Britain. No one knows for certain, although the epidemic got its name because Spain was particularly hard hit.

By the time the epidemic had run its course in 1919, four waves of the disease had claimed 20 to 50 million lives worldwide and 675,000 Americans.

The North Country, including Tower, escaped the first wave, but not the second that came in the fall. Publisher Frank C. Burgess chronicled the toll the epidemic took on life in Tower and Soudan in the pages of the Tower Weekly News, printed every Friday, and although the surge was over and gone in a little more than a month, many of his descriptions read as portents of the coronavirus pandemic of 2020-21.

Beginnings

The first inkling of influenza was a simple line in the Oct. 11 local news items: “Mrs. Geo. Kitto is quite sick with the grippe.” Illnesses and hospitalizations in those days were news to be shared, unlike the strict confidentiality of health information today.

On the front page of next week’s newspaper Burgess featured a large informational piece about Spanish influenza, written by physician and Board of Health member R. L. Burns, who concluded the article by saying, “Fortunately, Tower and Soudan have so far escaped the epidemic, but there is cause for vigilance and care.” Perhaps of greater immediate interest was a report that electricity service was being curtailed temporarily because of low water levels in the Pike River and reservoir that powered the generator.

Epidemic strikes

There wasn’t an Oct. 25 edition in the Minnesota Digital Newspaper Hub holdings, but it was clear from the abundance of news in the Nov. 1 newspaper that influenza had grown into a major problem.

Burgess published a proclamation from Mayor I. G. Ketcham closing the schools and directing “all people be and are hereby requested to remain within the private boundaries of their respective domiciles” – a quarantine. Ketcham’s order was far-reaching, closing “the local theater, all lodges, churches, gatherings and meetings of every kind.” Businesses could remain open but were directed not to allow any people to congregate.

Seven individuals with varying degrees of influenza were named, with only one, William Holter, reported to still be sick. No new cases had been reported since Tuesday, Oct. 29, and Soudan was said to be entirely free of it.

However, the Vermilion Lake Indian boarding school was a different story.

“Vermilion Lake Indian school has been a veritable hot-bed for the disease, however, there having been as many as 31 cases there at one time since it was first discovered last Saturday.” Two deaths at the school were reported – 12-year-old Ellen Boyd and the six-year-old daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Jack Sam.

Conditions had also been dire in Ely, Burgess reported.

“Matt Herranen, who is in town today from Ely, says the influenza epidemic there is still a serious problem, although no new cases have been reported since Wednesday. A large number of deaths have occurred, however, these ranging from four to seven daily for a week or more.”

The Nov. 8 edition of the paper had more sad news. William Chester Holter, 21, and Indian school student Rhodie Calf, 6, died earlier that week.

Dr. Burns was featured again, this time with a grim assessment.

“The general situation is far worse than is represented and is likely to be even worse in the immediate future,” he wrote. “We want to get everybody inoculated as soon as possible. There is a liberal supply of the vaccine at both Tower and Soudan hospitals, furnished by the Steel corporation, and everyone there is urged to make use of it.”

Information about social restrictions was repeated, and this time an additional precaution was added for businesses.

“Persons in business houses who are daily coming in contact with patrons and are inside most of the time should wear handkerchiefs or masks over their mouth and nose as a protection.” Masking when caring for an infected person had been recommended weeks before.

As the world celebrated the news reported in the Nov. 15 Tower Weekly News that the “GREAT WORLD WAR IS OVER,” locals also mourned the news of the passing of 24-year-old Miss Maude Campaigne, daughter of Mrs. W.H. Campaigne, who died at the McIntire hospital in Virginia. The families of more than 3,000 healthcare workers who have died from COVID-19 could sadly empathize with Mrs. Campaigne, as “When taken ill, Miss Maude was engaged as head nurse at the hospital in which she died, a position she had held for several months.”

Winding down

By the time the Nov. 22 edition was published, the general consensus was that the epidemic was on the decline in Tower and Soudan. Dr. Burns compiled a report of the extent of the epidemic up to that point. He counted 50 cases in Soudan, 23 in Tower, and 39 at the Indian school. Four deaths were reported at the Indian school, none in Soudan, and one in Tower. The Tower death toll Burns reported was in conflict with previous newspaper reports. Soudan had 670 people vaccinated and Tower had 525, but none were vaccinated at the Indian school.

The news was mixed again on Nov. 29 when the mayor rescinded restrictions and “the lid was taken off everything except dancing. Tower and Soudan have indeed been fortunate and if our good luck will only continue there will be double reasons for rejoicing.”

However, there was also the death of another young woman to report.

“Mrs. Sophia Maki, age 32, died last evening at her home on North Third street. Mrs. Maki was taken ill just a week ago with influenza, from which pneumonia developed, but was getting along nicely until yesterday morning when she gave birth to a baby boy. In her weakened condition she was unable to withstand the ordeal.”

But by the first week in December, news of the epidemic was reduced to a single paragraph in the local news items on the back page of the paper.

“Tower, Soudan and the Indian school are entirely free of the influenza,” Burgess wrote. “There has not been a new case at either place for more than two weeks. There are a few cases in the nearby farming districts but conditions there have improved greatly over a week ago and the disease appears to have about spent itself in this district.”

From beginning to end, the influenza epidemic held sway in Tower, Soudan, and the Vermilion Lake Indian school for about two months, 12 months fewer than COVID-19 has been threatening health, claiming lives, and disrupting daily lives here and across the country. One can only wonder if the coronavirus will have the longevity of the many strains of the influenza virus that live on since the disastrous “grippe” that held the entire world in its sickly grasp.