Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

Telling Jizz from Jazz

What an albino robin says about truth and perception

I saw a bird flash through the crown of an aspen, ruffling summer leaves, briefly lit by morning sun. At that instant I thought: robin. I’d keyed off the shape, size, and location. In the next …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

Telling Jizz from Jazz

What an albino robin says about truth and perception

I saw a bird flash through the crown of an aspen, ruffling summer leaves, briefly lit by morning sun. At that instant I thought: robin. I’d keyed off the shape, size, and location. In the next instant I thought: but it was white, pure white! I had seen the bird for no more than three seconds.

In the birding lexicon there’s a phrase “general impression and shape” or G.I.S., spoken as “jizz.” It’s commonly a snap judgement, and experienced observers almost always have a jizz when they glimpse or hear a bird. That first impression may be wrong, but it registers. If my jizz was correct then I’d seen an albino robin. Is that even possible? Yes, there are albino birds, and according to data from the University of Wisconsin, robins express full or partial albinism more than any wild bird species. Just over eight percent of North American avian albinos are robins, and about one in 30,000 individuals show the trait.

So my jizz was likely trustworthy, but here’s the thing: I wasn’t casually strolling the woods that day, I was stalking. About 200 times each year I deliberately spend an hour in a specific area, seeking every bird I can see or hear and recording species and numbers that I enter into an international data base accessed by research ornithologists. For that purpose jizz is not enough. As bird identification expert David Sibley writes, “Observers should beware of using jizz as a substitute for careful study and thought.” I’m confident I spotted an albino robin, and enjoyed telling people about it, but I did not record the observation as fact. My sighting was as much jazz as jizz, a kind of happy birding riff. Those three seconds were fun but they weren’t science. If the bird had perched, and if I had a few more moments to raise and focus binoculars, maybe then I could’ve logged the sighting.

We regularly employ jizz in daily life, reaching quick judgments about people, ideas, news items, food, music – you name it. It’s a seemingly automatic process. You meet a new person, experience an impression, and categorize them. It can be a useful short cut as we traverse the obstacle course of life. Is that new person a potential ally or a potential adversary? But the problem with short cuts, rules-of-thumb, and other heuristic schemes is that by definition, they lack nuance – subtle distinctions or variations. Election campaigns are the obvious case in point, driven by sound bites, glittering generalities, and blatant appeals to bias. It’s possible that facet of our national democratic process will never be remodeled, but such disarray is not mandated for your personal life.

It’s my experience that on a smaller scale even politics can dodge the downside of jizz. For over three decades I’ve been heavily involved in township government, and on several occasions I’ve witnessed citizens enter the meeting chamber in a polarized, sometimes hostile mindset over a local issue. Given the relatively few people involved and town board members who were willing to listen, and to entertain details and shades of gray – that is, nuance – on almost every occasion an amicable, if not perfect, resolution was achieved. You could see it happening – the softening of brows and pursed lips; sentences beginning with “Well….” or “Oh, I didn’t know….”; a ripple of self-conscious chuckling. The essential leavening was good will and a sense of responsibility.

Manifestations of good will and responsibility are not routinely generated by jizz. We aren’t born with a sense of duty or a sturdy streak of amicability. If we’re seeking a durable outcome in the human sphere, allowing nuance to blossom, then we usually need to take more time, uncover enough truth to be able to “log in the sighting.” It’s crucial work. Mark Twain wrote, “A lie can travel around the world while truth is putting on its shoes.” He said that a century before the internet. Barbara Kingsolver, another insightful writer, remarked, “Pain reaches the heart with electrical speed, but truth moves to the heart as slowly as a glacier.” It would be facile and perhaps old fashioned to advocate therefore that we should read more books and fewer social media posts. I support the notion, but it’s unrealistic. That ship has sailed and is over the horizon. I need to keep in mind that my jizz on this matter is informed by the facts that I’m an aging Boomer who reads, on average, a book per week; who long ago deleted the Facebook account; who has never Tweeted. And yes, I certainly know intelligent, reasonable humans who don’t routinely read books.

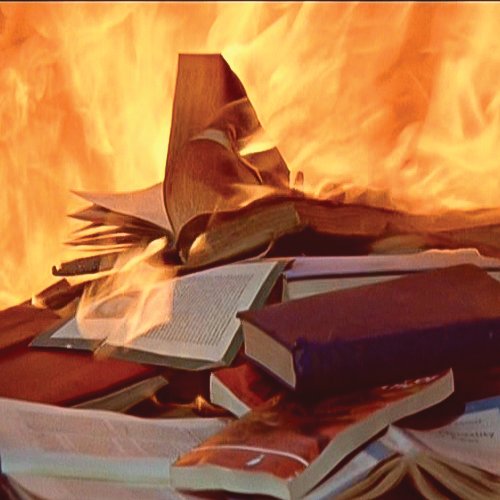

However, are their lives and our culture and civilization supported by those who do? It’s worth thinking about. Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel “Fahrenheit 451” describes a future American society where books are outlawed and routinely burned by “firemen” appointed to the task. It’s a passionate parable about censorship and oppression, and one of the more chilling aspects of the tale is that most citizens don’t have a problem with it. While actually torching mounds of books is an effective plot device, and certainly happens in our world, Bradbury himself noted that, “You don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them.” I submit that’s a way to either purposely or inadvertently create a national, communal, unconscious jizz.

It’s been done. Adolf Hitler wrote: “The art of leadership consists of consolidating the attention of the people against a single adversary and taking care that nothing will split up this attention….The leader of genius must have the ability to make different opponents appear as if they belonged to one category.” In other words, dispense with nuance. Which is pretty much the same as eliminating individual ideas and expression. It’s not a long journey from there to the gallows. If not in practice, at least in effect. If you’re afraid to say something, you don’t need to be executed. When people in contemporary America attend meetings carrying guns, it usually doesn’t bode well for dialogue over the details. Openly discussing details is the hard currency of retail politics, the social legal tender that keeps communities together.

I once had a .44 Magnum revolver aimed at my forehead. The muzzle was an intimate eight inches away. I was ordered to “Keep your mouth shut!” I did. The threat was not issued in a political context, but when shock subsided I recalled a famous statement by Mao Tse-tung. “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” The man brandishing the .44 was in not in a symposium-friendly mood. If his trigger finger had twitched I would’ve been dead a half-century ago, a victim of impulse. But fortunately, power doesn’t flow exclusively from force or threats. Margaret Atwood, one of the great decoders of the human condition, wrote, “A word after a word after a word is power,” that is, the relentless pursuit and application of truth. Books are only one source of such power, but over the long haul what channel is deeper, or to update the metaphor, what channel has more bandwidth?

Last October I looked out a window and spotted a bird scratching in the duff at the base of a balsam fir. My jizz: what is that? I’d not seen this bird before. Shape suggested a Brewer’s blackbird, but it wasn’t. I scrutinized it with binoculars from twenty feet away for a solid three minutes – a relative eon in birding. Aloud, I recited the characteristics of its “topography,” then grabbed a field guide and ticked them off against three or four images, employing Sibley’s “careful study and thought.” It was a rusty blackbird. No doubt. I logged it in.