Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

Does Twin Metals really have a viable plan?

Even as the company seeks redress in the courts, critics say their mine plan is broken

REGIONAL— In legal filings and in public statements, representatives of Twin Metals have argued in recent months that they have a viable and environmentally-safe mine plan of operations, or …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

Does Twin Metals really have a viable plan?

Even as the company seeks redress in the courts, critics say their mine plan is broken

REGIONAL— In legal filings and in public statements, representatives of Twin Metals have argued in recent months that they have a viable and environmentally-safe mine plan of operations, or MPO, that’s been submitted and is ready for environmental review. They argue that the company’s investors have sunk over $500 million into exploration, engineering, and other development costs to bring the project forward, and that they should have the right to a project-specific review of their plan to build an underground copper-nickel and precious metals mine near Ely.

However, critics of the proposal, and its potential impact on the 1.1-million-acre Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness located downstream of the proposed mine, are dismissing those claims. They argue that the company lacks a viable mine plan to study and has yet to demonstrate it can operate its mine without significant environmental impacts, most notably to the Boundary Waters.

Meanwhile, the company has failed to demonstrate publicly that its proposal is economically viable, since Twin Metals has yet to release financial projections based on their current mine plan.

Twin Metals, which is owned by Chilean mining giant Antofagasta, did submit an MPO to the Department of Natural Resources and the Bureau of Land Management for review back in December 2019. DNR officials spent more than two years analyzing the information submitted by the company, but never concluded that the information was complete enough to issue a draft scoping document.

Barb Naramore, a DNR assistant commissioner, said it is not uncommon for her agency and a proposer of a major project to have several rounds of comments and responses before the agency is ready to issue a draft scope, which forms the foundation for an environmental impact statement. As it stands today, some significant issues between the DNR and the company remain unresolved.

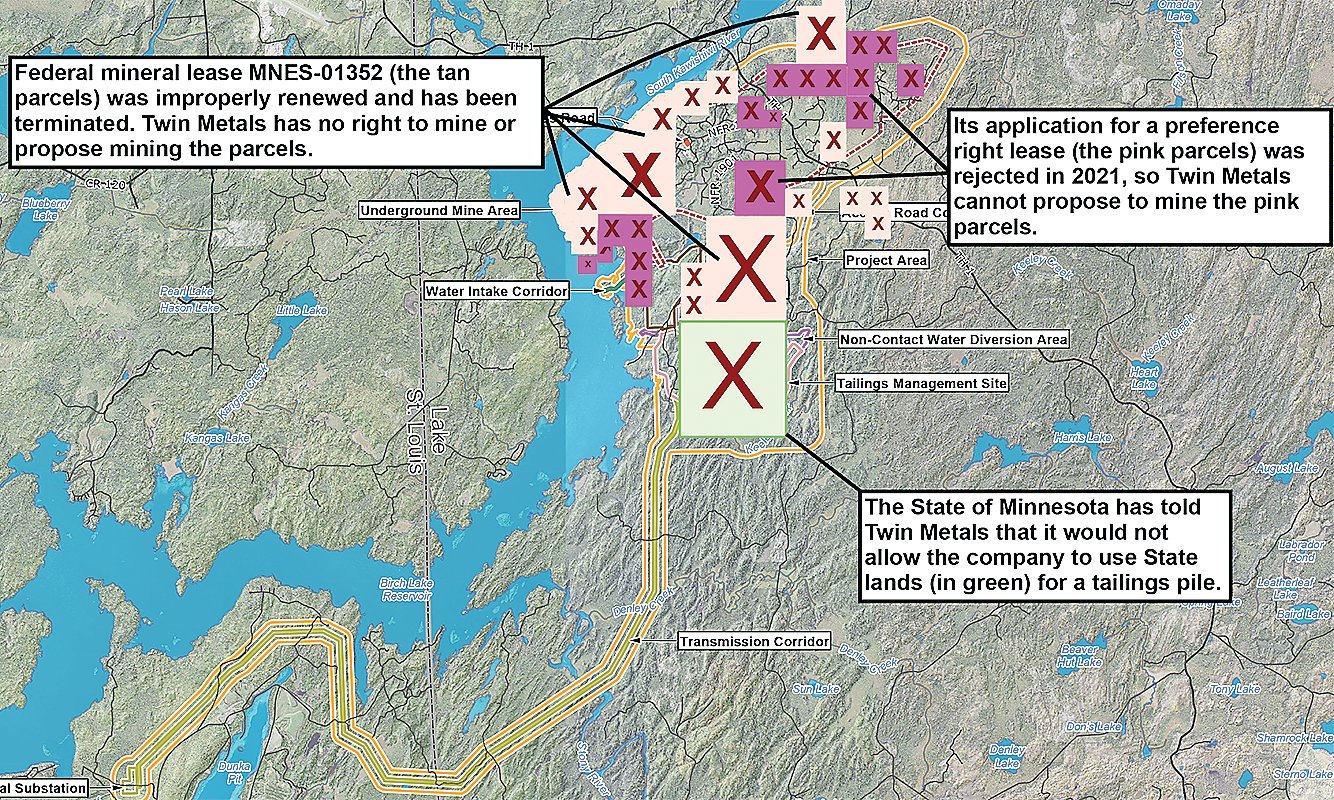

At Twin Metals’ request, the DNR halted its initial analysis of the MPO last February after the Biden administration canceled two federal mineral leases critical to the project. It’s that administration decision that is being challenged in the lawsuit filed by Twin Metals last month. Yet even were Twin Metals successful in its legal efforts, which appears unlikely, it’s still not clear they have a viable mine plan that regulators could review.

Indeed, the DNR has already informed Twin Metals that it is unlikely to allow the company to site its proposed tailings facility on state lands, as called for in the latest MPO. “Based on information available to date, the DNR has determined that Twin Metals’ currently proposed location for its tailings facility would potentially encumber School Trust mineral resources,” wrote DNR Commissioner Sarah Strommen in a Feb. 15, 2022, letter to Twin Metals CEO Kelly Osborne. “Furthermore, the DNR believes this use would pose an unacceptable financial risk to the state and potentially to the School Trust Fund. The DNR has notified the Office of School Trust Lands of our concerns with the proposed tailings facility location,” concluded Strommen.

Much of the DNR’s concern regarding the safety of the tailings stems from Twin Metals’ proposal to utilize so-called “dry stacking” of its tailings. The company has touted its proposal to use dry stacking as a safer method of tailings disposal, but the DNR concluded as recently as 2018 that dry stacking is not appropriate given northern Minnesota’s wet climate. In a detailed, 67-page dam safety finding and order issued by the DNR in regards to PolyMet Mining’s proposed NorthMet copper-nickel mine, the DNR concluded that dry stacking may be a sound option in an arid or arctic climate, but not in Minnesota.

“In a wet climate, dry stacking has major environmental disadvantages,” concluded the DNR. “Maintaining dry stacked tailings as “dry” in areas with substantial precipitation and/or a high-water table is difficult. Once exposed to rain or snow, the dry stack becomes wet, so most of the benefits of dry stacking are lost. Dry stacked tailings that become wet again (but are not submerged) are subject to oxidation and leaching of heavy metals. As precipitation then intermittently washes through the tailings, those heavy metals and other constituents may be washed into surrounding soils and nearby water bodies.”

In congressional testimony earlier this summer, Julie Padilla, Twin Metals’ chief regulatory officer, argued in written testimony to the House Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources that the mine had “no potential for acid rock drainage,” (emphasis in the original), although she appeared to walk that back in her oral testimony to the committee.

The DNR’s Naramore says her agency has not confirmed the company’s claims. And given the state’s expressed concerns about the proposed location and the method of tailings disposal, it appears state regulators are skeptical at the very least.

So are other experts in acid drainage. During a Senate hearing this summer, Dr. Paul Ziemkiewicz, Director of the West Virginia Water Research Institute, acknowledged under questioning that the Twin Metals mine and its tailings posed an almost inevitable risk. “By definition, it’ll be wet enough to generate acid mine drainage,” he told senators. Other well-regarded experts in the field have concluded in published studies that the proposed mine posed a substantial risk of polluting downstream waters, given the complex geology and abundant water in the region.

For Twin Metals’ critics, the concerns of the DNR and other experts simply confirm their own doubts about the company’s claims regarding the potential for acid rock drainage and suggest the company’s claims to have a sound and viable plan are little more than corporate spin.

“The propaganda pitch by Antofagasta’s Twin Metals and its allies is as baseless as their lawsuit,” stated Becky Rom, national chair of the Ely-based Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters. “They demand environmental review of a hypothetical mining project that is not viable. It doesn’t possess the leases it depends on and, thanks to the wisdom of Gov. Walz’s administration in prohibiting the use of state land, it has no place to put its toxic tailings.”

Twin Metals cites the work of Rens Verburg, of Golder Associates, a well-known expert on acid mine drainage, who argues that not all sulfide-bearing rock is the same. “The ARD potential of mine materials is determined by the balance between the acid generation potential of a material (i.e. sulfide concentration) and the neutralization potential,” according to an executive summary of a paper produced by Verburg on behalf of Twin Metals. Verburg said his analysis of the sulfide ores at Twin Metals’ Maturi deposit found that the most abundant type of ore, known as copper sulfide chalcopyrite, oxidizes at a slower rate than other types of sulfide and may not generate acid upon oxidation given its higher potential for neutralizing acid. “As such, the potential for [acid rock drainage] generation of the Maturi deposit due to sulfide oxidation is much lower than other types of deposits containing sulfide,” he concludes. Verburg subsequently produced an editorial for Twin Metals that highlighted his conclusions, which was used in Twin Metals’ public relations efforts.

DNR experts have made it clear that while they recognize that some of the minerals that Twin Metals hopes to mine do have some buffering capacity, they appear far from agreement on how much and on how long that buffering capacity might last. In the end, DNR’s experts appear to agree that the material in question will eventually leach acid— it’s only a matter of time.

A long-term DNR-commissioned study of acid drainage potential on the Duluth Complex, where the proposed Twin Metals mine would be located, cautioned that only long-term analysis, like that undertaken for the DNR study, can provide any real certainty about the potential for acid drainage. “Emphasizing this point, drainage pH from one sample was circumneutral for 800 weeks (or 15 years) and then acidified, reaching a minimum pH of 3.8,” noted the study. That study also found considerable variability in test results, depending on whether samples were tested in the field or in a laboratory.

Financial questions

In any analysis of a proposed mine, the financial viability of the operations is critical to ensuring that the mine doesn’t become a financial liability to taxpayers either during operation or after closure. While the DNR does not require financial projections as part of the environmental review portion of permitting, it does look closely at financial viability before issuing key permits since the company would need to demonstrate its project would generate sufficient cash flow to finance a closure plan and other identified mitigations.

Not every agency takes that approach, however. In fact, the U.S. Forest Service declined to include a possible underground operation as a studied alternative in the environmental review of PolyMet’s NorthMet project back in the 2000s because the agency concluded an underground operation was not economically viable.

Twin Metals’ own documents have raised doubts about the financial viability of its underground operation. Financial estimates released by Twin Metals in 2014 as part of a prefeasibility study (known as an NI 43-101) showed economically marginal returns on an earlier version of their mine plan. Stock in Twin Metals’ former parent company, Duluth Metals, collapsed in the wake of the release of the plan and the subsequent announcement by Antofagasta, which had been the project’s primary financial backer, that it would not exercise an option to buy a greater share of the company. Antofagasta later purchased outstanding shares in the company for pennies on the dollar, assuming primary ownership of the venture.

The latest mine plan calls for more limited production, of approximately 20,000 tons per day (tpd), compared to the 50,000 tpd production rate analyzed in the 2014 prefeasibility study.

Twin Metals did not directly respond to questions on its financial projections or whether any have been completed. Company spokesperson Kathy Graul noted that the company’s environmental review is currently on pause and that any need for such projections as part of the permitting process would likely be “years away.”

Even so, mining ventures are often eager to tout good economic data. PolyMet, for example, has publicly issued at least three financial estimates since 2008. While the most recent projections showed a substantial decline in overall profitability and return-on-investment than earlier versions, all three of its projections surpassed the marginal returns contained in Twin Metals’ 2014 NI 43-101 report.

Investment lost?

Twin Metals representatives have made note in the media as well as in legal filings that the company has invested more than $500 million over the past decade to advance their project. The vast majority of that investment was made by Antofagasta, a foreign multinational company that has generated nearly $50 billion in revenue over that same period.

While Twin Metal’s original parent company, Duluth Metals, did attract a limited amount of small investor dollars prior to 2014, those investments were lost primarily as a result of Antofagasta’s strategic moves in the wake of the issuance of the prefeasibility study and would not be recovered even if the mine were to move forward.

Critics of the mine proposal express little sympathy for any lost investment on the part of Antofagasta. Rom noted that the NI 43-101 report that Twin Metals issued in 2014 clearly stated that the renewal of its two federal leases was discretionary on the part of the Bureau of Land Management. “My take is they made a business risk decision,” she said. “They went into a deal knowing the lease renewal was discretionary on the part of the government and knowing there was serious public concern about the plan.”