Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

The history of Co-op Point

EMBARRASS- It was a full house at the Sisu Heritage Annual meeting, held at the Embarrass Town Hall on Feb. 16, and a time to celebrate the cultural contributions of Finnish immigrants to the …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

The history of Co-op Point

EMBARRASS- It was a full house at the Sisu Heritage Annual meeting, held at the Embarrass Town Hall on Feb. 16, and a time to celebrate the cultural contributions of Finnish immigrants to the Embarrass area.

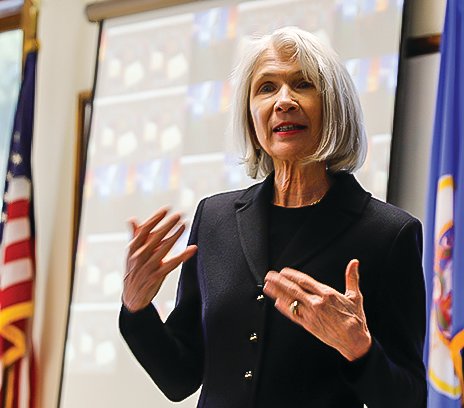

Valerie Myntti, of Eagles Nest, was featured to present the history of the Finnish Cooperative Movement in the area and her family’s connection to Co-Op Point on Eagles Nest Lake One. Co-op Point was a summer oasis created by a group of Finns from Ely. It included small private cabins, a summer camp for children, and a place that Finns from across the area were welcomed to come and camp on the lakeshore.

While Myntti told the audience she is by no means a professional historian, her interest in her family’s Finnish roots has drawn her to study the cooperative movement on the Iron Range.

Her family’s personal story was a mirror of many Finnish immigrants to the Iron Range.

“While there are many shared experiences,” she said, “Finns are not a monolithic group.”

According to her research, during the period between 1880 and 1930, about 240,000 Finns emigrated to the United States.

In 1917, Finland declared independence from Russia, which had taken control of Finland back in 1809. A civil war followed, with the population split between two opposing world views.

“White Finns,” she said, “were supported by the German army, and consisted generally of middle class and wealthier elites.” Many spoke Swedish and were politically more conservative and more church-going.

“Red Finns were the socialist working class,” she said. “These were the commoners, laborers, agnostics and atheists, along with intellectuals with ideas of utopia.”

Both classes of Finns ended up settling on the Iron Range and in Ely. Her family identified with the Red Finns. On the Range, she said, both groups mostly got along.

“The working class summered at places like Co-op Point and shopped at coops. The wealthier Finns summered at Burntside Lake, but they had their own shops and clubs.”

Finns were instrumental in creating many of the cooperatives that still are visible in the area today. Myntti’s great uncle ran the Pike-Sandy Coop. They were also strong labor union advocates. Finns were often blamed for labor unrest.

“They led the struggle for better wages and working conditions,” she said. “Some considered them subversive troublemakers.”

The Finns were not anarchists, she noted. They were in favor of cooperative communitarianism.

“No word strikes more fear in the hearts in America than socialism,” she said. “But the Finnish world view was progressive: cooperative ideology, socialist values, morally conscious economies, justice, and economic security for all.”

“Socialism is already entrenched here,” she said, “and people like it. When the government intervenes to set working hours, child labor laws, and Social Security, that is socialism at work.”

Myntti said the novels of Charles Dickens show what life was like without socialism.

“We must banish our fear around socialism,” she said. “It has been weaponized for political reasons. The real debate isn’t capitalism vs. socialism, but the appropriate balance between them.”

The Finnish cooperative movement was based on a need for self-determination.

“Company stores and local merchants sympathized with the mining companies,” she said, “and they would not give credit to Finns during times of strikes.”

Coops were created with common ownership.

“Finns banded together to help themselves,” she said. “It was an alternative model to capitalism. They still needed to make a profit. They paid their shareholders a small quarterly dividend.”

Cooperatives were an essential part of the rural community. They included general stores, dairies, coffee companies, restaurants, and credit unions. They built theaters, published newspapers, libraries, nursery schools, and ran summer camps, she said.

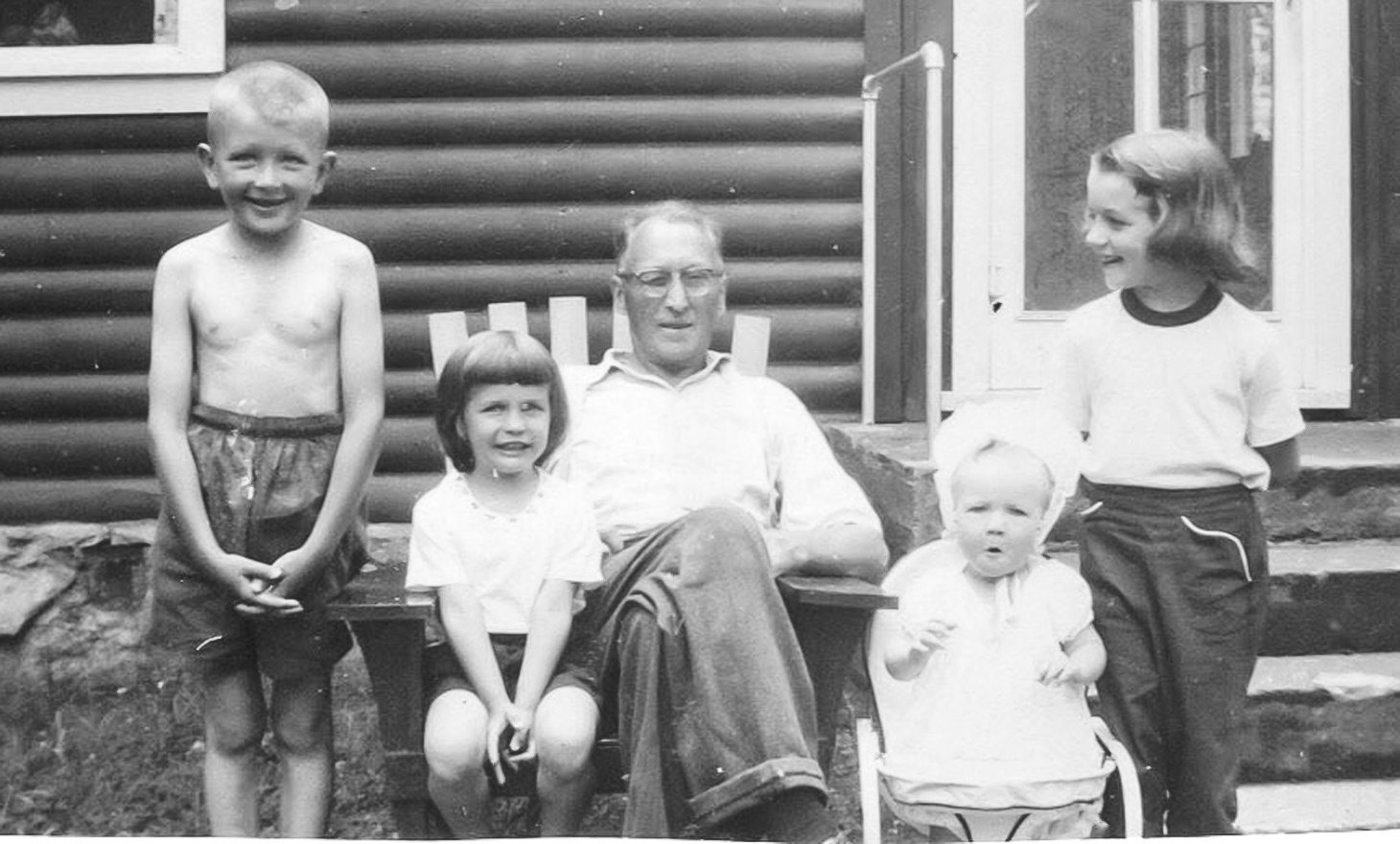

Myntti’s grandfather was part of a group of 20 families who bought a large area of lakeshore on Eagles Nest Lake One back in the late 1920s. They each paid $50 for a small lot, where they built rustic cabins. The rest of the land was owned cooperatively. It was the first home her grandfather owned.

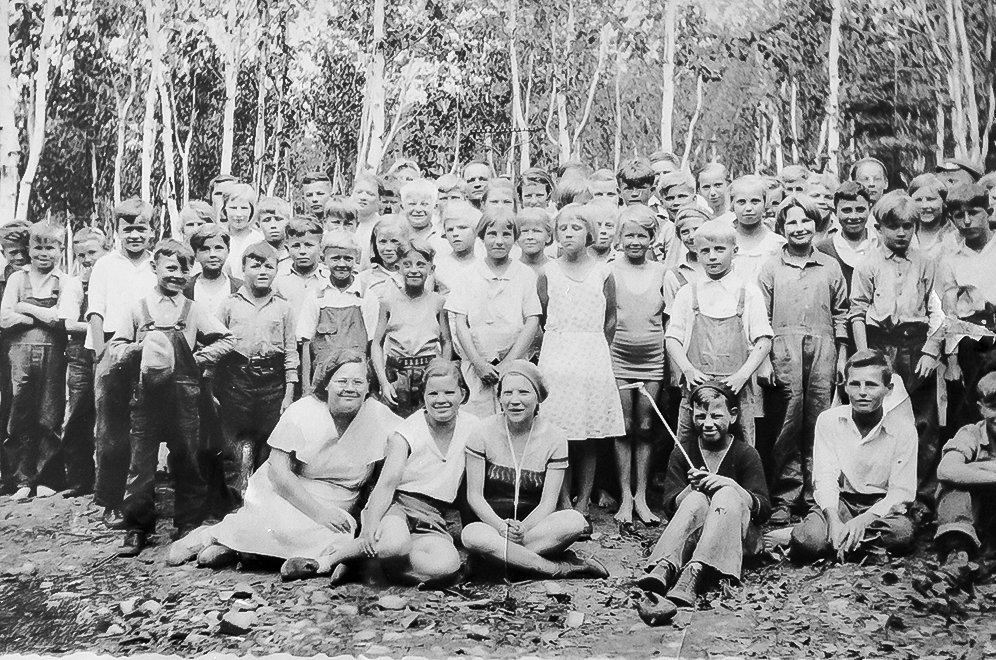

“They created a coop park where workers and their families could come and pitch a tent for a vacation at the lake. They also operated a summer camp for children.”

“My father and his sister attended the camp,” she said. “They taught classes in Finnish, and the campers learned about helping their neighbors. They were immersed into the cooperative philosophy.”

The camps included music, arts and crafts, swimming, and drama.

“Finnish workers came from all over for their summer holidays,” she said. “There were communal feasts, and they put on concerts.”

Donald Myntti, Valerie’s father, was a 1941 graduate of Ely High School. He died last year, just short of his 99th birthday.

“My dad believed he had the most wonderful childhood in the country,” she said. “He marveled that Co-op Point existed at all, even during the Depression.”

Myntti said children were treated as “precious gifts” while at the camp.

“They were shielded and protected from all the hardships their parents endured,” she said. “The lakes and forests were true gifts.”

At the time Co-op Point was being developed, there was a train that traveled from Ely to Tower, which is how most members got there and back.

Co-op Point flourished into the 1950s, but by that time, people had become better off. Her own family sold their small lot and cabin in the early 1960s, when her grandparents were too old to navigate the steep rise between the lakeshore and their cabin site. But they used the proceeds from that sale to purchase a more level lot and cabin on Eagles Nest Lake Three, where Myntti and her husband now live.

Mesaba Coop Park, near Hibbing, is still in operation today, and was developed alongside the same model as Co-op Point. Mesaba Co-op Park still offers a summer camp for children, along with affordable camping for families, and hosts an annual Midsummer celebration each year.

Annual meeting reports

President Marlin Bjornrud reported on the nonprofit’s activities in 2022. Sisu Heritage maintains and restores historic buildings in the Embarrass area. They sponsored concerts at the housebarn and at the Apostolic Lutheran Church, two historic buildings they now manage; hosted National Sauna Day; had new historic informational signs made to replace aging ones; and managed the Nelimark Museum building.

Attendees heard updates on fundraising and grant writing, and plans for the continued restoration work at the Seitaniemi Housebarn.

The Farmstead Artisans group donated over 800 hours of their time keeping the Nelimark open, hosting over 1,500 guests, not counting the crowds that showed up for the Nelimark Christmas Open Houses in November and December. The Nelimark had $36,000 in sales of locally-made crafts, baked goods, and other items of cultural interest.

“Since Four Corners went away,” Bjornrud said, “it has become the hang out place.”

Visitors were introduced, including Ahti Westphal, a project manager for DJR Architects in the Twin Cities. He had come up to Embarrass to visit the historic Seitaniemi Housebarn and had snowshoed around the site before the annual meeting.

Westphal said he had fallen in love with old wooden buildings when he was a child. His family had an island on Rainy Lake, and took a trip to visit the historic log buildings when he was a young child.

“I’ve dreamed of coming here for over 20 years he said, “The work you do, it is quiet work, but is has an incredibly deep impact on people you might not even know.”

“I can’t thank you enough,” Westphal said. “I want to learn more about Sisu Heritage.”

“People like you keep us from taking it for granted,” said Bjornrud.

St. Louis County Commissioner Paul McDonald said the work of Sisu Heritage makes him proud to honor the heritage of his mother, “a full-blooded Finn.” He said he is working with the county board to increase funding for the St. Louis County Historical Society and its partner organizations, like Sisu Heritage.