Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

The big iron strike that wasn’t

Three years of painstaking digging failed to yield a productive vein

PINE ISLAND- An abandoned mine shaft identified in 2019 on Lake Vermilion’s Pine Island that was once touted as having the potential to be “one of the largest mines on the range” …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continue |

The big iron strike that wasn’t

Three years of painstaking digging failed to yield a productive vein

PINE ISLAND- An abandoned mine shaft identified in 2019 on Lake Vermilion’s Pine Island that was once touted as having the potential to be “one of the largest mines on the range” turned out to be one of the biggest mining speculation busts instead.

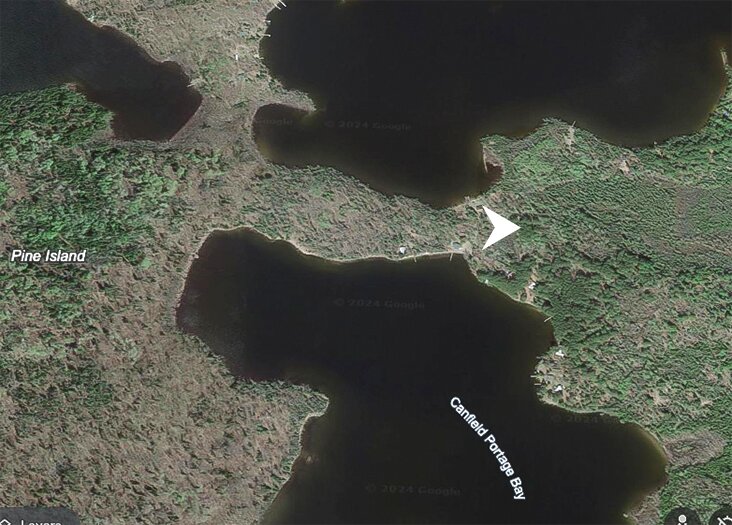

As reported in the Timberjay in 2019, Pine Island landowner Wayne Dahl reached out to St. Louis County officials in 2018 about what he thought at the time were water-filled exploratory pits on property adjacent to his near Canfield Portage. He was planning to build a lake cabin on his property but was concerned about the hazard the pits would present for his visiting grandchildren. The pits were on tax-forfeited property, so it fell to St. Louis County to remedy the situation.

When county mine inspector Derek Harbin visited the site in August 2019, the smaller pit proved to be about 12 feet deep. When he tried to measure the larger of the pits, his 100-foot tape measure wasn’t long enough, and with additional clues in the immediate area, it wasn’t hard to conclude that the pit was actually a mine shaft.

Needing to remediate the hazard, Harbin looked at various options before choosing a traditional one — backfilling the hole by using the material from a nearby waste pile, at a cost of about $14,500. It was around Halloween in 2019 and the fill operation took two or three days, Harbin said.

“The dump truck was dumping and dumping and dumping and we got through day one and I still wasn’t getting anything on the 100-foot tape measure,” Harbin said. “We’re watching the pile dwindle and still weren’t getting a reading. Ultimately it took that entire spoil pile, and our estimate was around 300 feet for that shaft. Someone did find a little bit of information regarding this and that was the measurement they had as well. It took nearly all the pile back in until we were able to get a mound on top of it.”

Before the backfilling began, Harbin coordinated with the DNR and Natural Resources Research Institute geologist Dean Peterson to have the site assessed. “It was great that we were able to get the geologists out there to document everything appropriately and make sure that we did our due diligence from a historical mine relevance point of view,” Harbin said.

Peterson told the Timberjay at the time that there appeared to be no record at all of the mining operation on the island.

His assessment pegged the date of the mine to the late 1800s or early 1900s and ruled out initial speculation that it might have been associated with the gold rush era in the late 1860s.

Mine history

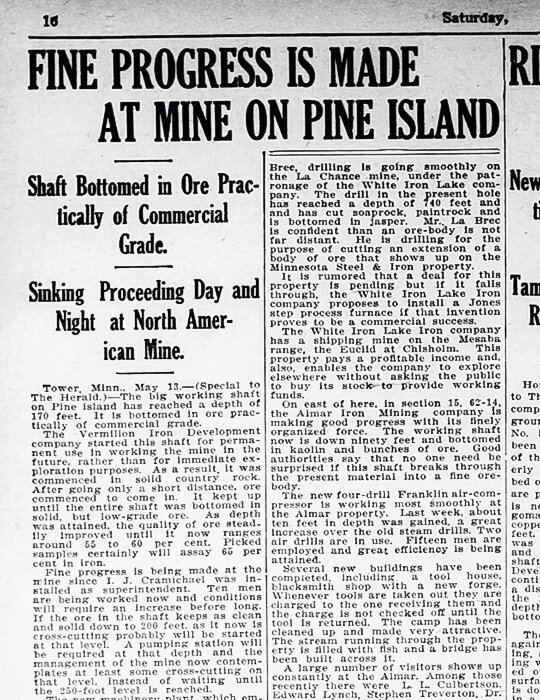

While there initially appeared to be no documentation of the Pine Island mining operation, a sharp-eyed Timberjay reader, Harold Poylio, recently forwarded an image from the front page of the May 13, 1911 Duluth Herald, which contained a story on the mine and the hopes that it could become a major iron producer. Additional research by the Timberjay together with accounts from various newspaper reports found in the Minnesota Historical Society’s Digital Newspaper Hub, uncovered more of the interesting story of this mine that never hit the big time. Where conflicting information was found, usually in the reported depth of the shaft, the Timberjay selected the data that appeared most consistent with the overall reported progress.

Initial interest in the possibility of a Pine Island mine came about when Albert and A.S. Kitto secured the title to a tract of island property in 1900 with the belief that it would someday prove valuable for its mineral resources. They sold two-thirds interest in the property to two Duluth mining men for $11,000, and then they collectively leased it to the Biwabik Mining Company in 1906 for exploration and possible mine development. The company drilled for eight months but did not find “anything of importance,” according to an article in the May 31, 1907, Tower Weekly News.

But that didn’t deter another group from taking a chance on Pine Island. In September 1909, Duluth entrepreneurs James Cardle and Tilton Lewis joined forces with Dr. T.F. Rodwell, a physician and superintendent of the Vermilion Lake Reservation School, Fredrick Merrill, of Tower, and Soudan mine superintendent Paul Chamberlain to form the Vermilion Iron Development Company (VIDC). They were encouraged by samples from surface trenching of the two veins of ore on the property that had iron content up to 61 percent, and the belief that the Pine Island veins were a continuation of the iron-rich Soudan formation. The company was capitalized for $750,000, with none of the organizers taking a salary.

Work on the mine shaft commenced in November 1909 and by the following April had reached about 45 feet. VIDC built a new machinery plant in May or June 1910 with a 70-hp steam boiler, a cylinder hoist, a two-drill air compressor, and a blacksmith shop, and in early July the now 65-foot-deep shaft was growing at about two feet per day, with 15 miners working two shifts. Some harder rock encountered by miners slowed that pace by half at the end of the month.

The ore being excavated was initially running well below the surface sample content, from 34 to 42 percent iron content as the shaft got deeper, but the trend was positive, as VIDC expected iron concentrations to grow the deeper they went. By November 1910 the shaft was 150 feet deep, and they had found some selected samples as high as 64.89 percent iron content, a level that on a consistent basis would be considered commercial grade. VIDC announced plans to start a crosscut tunnel when the shaft hit 200 feet, something that wouldn’t happen for another nine months.

By the summer of 1911, the mine-in-progress had become a popular tourist attraction for locals and travelers alike.

“Last Saturday, Mr. and Mrs. M. W. Hingeley of Floodwood and Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Carhart of Duluth were among the visitors at Pine Island, and the ladies donned the oilskin suits and miner’s hats and took positive pleasure in the trip to the bottom of the shaft in the big iron bucket. The shaft is down 175 feet at the present time, and the last 25 feet has been in commercial ore,” reported the Tower Weekly News at the time.

Reports coming from the mine gave encouraging news and predictions of great success. With that in mind, optimistic rumors grew of a possible Canadian Northern railroad line to be built from Cook and running alongside Lake Vermilion to Pine Island and then on east to Ely. A mine anticipated to be one of the largest in the region would surely need rail service to move its ore to market, people speculated.

The mine shaft reached 200 feet in late July 1911 after VIDC upped the ante by investing in a new electric generator to power six new electric drills as well as lighting for the mine and camp, and with promising finds of 62-percent iron content ore, VIDC began a crosscut tunnel to the north of the shaft. When the tunnel hit 70 feet in length in September, running through a mix of iron ore and jasper, company officials said they expected to hit the main ore body in 30-40 more feet. Instead, they dug 130 more feet, a total of 200, and never found what they were looking for. The ore was deemed “very satisfactory,” but wasn’t clean enough for sustainable commercial mining.

So VIDC went deeper, banking on their experience that the ore would continue to get better the deeper they went. In August 1912, they reached 300 feet, encountering a formation that included soapstone and quartz, and instead of mining another crosscut tunnel they widened the base of the shaft to accommodate a diamond drill, intending to bore in all directions in search of solid commercial ore.

Once again, they were unsuccessful. While industry journals in 1909 reported that VIDC was planning a 500-foot shaft, company officials apparently had seen enough and abandoned the project.

Unsurprisingly, the failure didn’t receive the same fanfare in the press that the persistent promise of success had. It wasn’t until March 1913 that the Tower Weekly News reported that the company “ceased operations at Pine Island last fall.” The quest for one of the richest veins of iron ore on the Vermilion Range had failed. VIDC had been reorganized as the Mutual Iron Company, and all the Pine Island equipment was being transferred to reopen the old McComber mine at Armstrong Lake, where they hoped to have greater luck.

And with that, the Pine Island mine faded from memory, masquerading as an excavation pit until over a century later its true nature was revealed by a man with a too-short tape measure. A unique bit of history uncovered, then covered again with the rock extracted to create it.