Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

September warmth

The data is clear: Fall is growing dramatically milder in the North Country

REGIONAL— Remember those September snows that never seem to fall anymore in the North Country? Remember when season-ending frosts were once common in late August or early September?

It isn’t …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

September warmth

The data is clear: Fall is growing dramatically milder in the North Country

REGIONAL— Remember those September snows that never seem to fall anymore in the North Country? Remember when season-ending frosts were once common in late August or early September?

It isn’t your memory that’s playing tricks on you, it’s the changing climate.

“Minnesota is warming across the board, and the warming is greatest over northern Minnesota,” said Kenny Blumenfeld, with the state climatology office. Blumenfeld spends about half his time as a climatologist studying climate change in Minnesota and he said the warming in recent years has been dramatic. Over the past thirty years, notes Blumenfeld, northeastern Minnesota has seen its average temperature in September increase by a whopping 1.1 degrees Fahrenheit per decade. “I have to tell you that’s an incredible rate of warming,” he said.

For those who garden, the change means an expanded growing season in a region where frost used to be relatively common after the third week of August. Old-time gardeners in the North Country remember the days when tomatoes rarely ripened before frost. Not any more. These days, it’s no longer unusual to avoid killing frosts through most, if not all, of September.

Each year, in effect, the region’s climate shifts a little further to the south. These days, the North Country experiences September weather more akin to Willow River, than Willow Valley, the rural township near Orr.

While the warming occurred slowly for many decades, the rate of change has increased sharply in recent years. According to Blumenfeld, the change isn’t as evident in high temperatures as it is in overnight lows. “We’re failing to cool off,” he said. “That’s happening more so than warming.”

That’s why the change is so noticeable in September, since it historically has been a month in northern Minnesota when temperatures cool fairly dramatically as the sun angle declines. “September is really the first month that normally feels like fall,” said Blumenfeld. “We would be losing more heat, but if there’s a little extra blanket of greenhouse gases, it holds in more of that warmth. It’s very consistent with the models for climate change.”

Data shows the trend

The temperature data across northeastern Minnesota show a undeniable pattern of warming, particularly since the turn of the century. Out of 122 years of recordkeeping in the region, five of the top ten warmest Septembers have been recorded just since 2004. The warmest September ever experienced in the region was in 2015, when the average temperature for the month hit an even 60 degrees F for the first time ever. That beat the previous record, of 59.8 degrees, set in 2009. This past September, which saw an average of 57.7 degrees, was the seventh-warmest ever recorded.

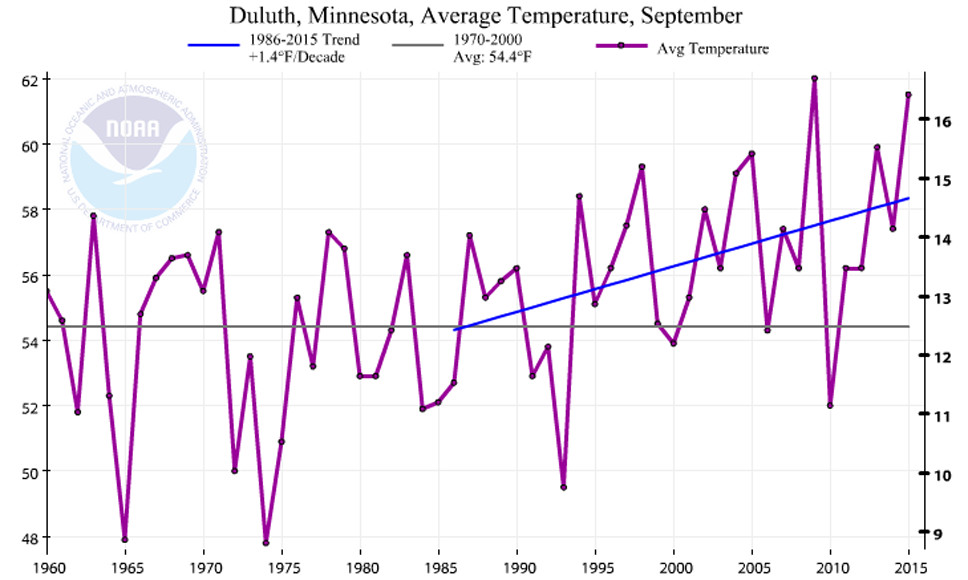

While regional data can be subject to change as locations of weather stations shift across the landscape, even long-time weather stations, such as those located at the International Falls and Duluth airports, confirm the change, although at different rates. At Duluth, the average temperature has jumped by a whopping 1.4 degrees per decade in September in the past thirty years. That’s a 4.2 degree F increase, or 2.33 degrees Celsius.

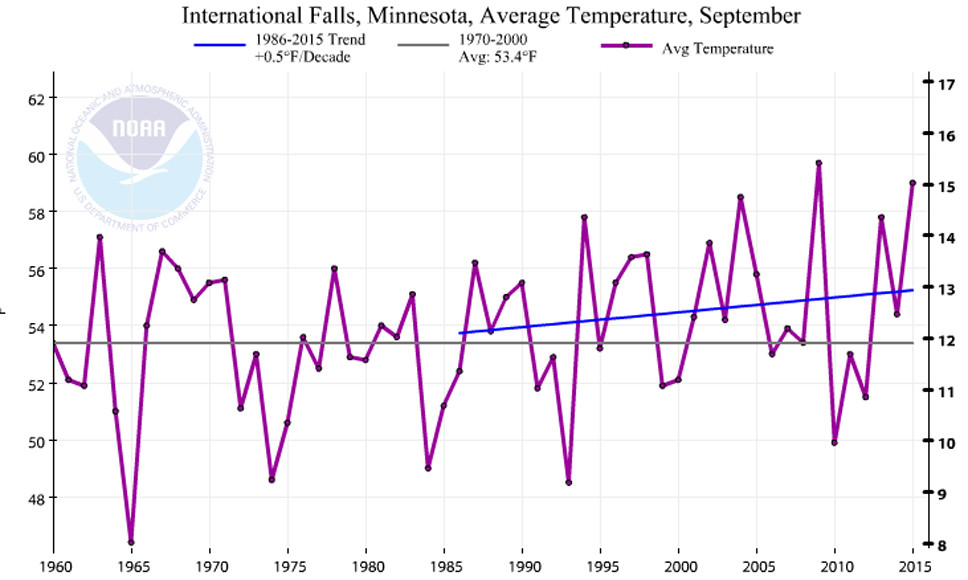

The warming during the same period has been less dramatic at International Falls, but still significant by climatological standards, increasing by an average of 0.5 degrees per decade, or 1.5 degrees over the thirty-year period.

Changing face of the region

While the changing climate, to date, has been a boon to gardeners who have benefitted from a longer growing season, the warming has already brought significant change to the makeup of the region’s forest. That’s according to Lee Frelich, a forest ecologist at the University of Minnesota, who has closely monitored forest composition in and around the Boundary Waters.

Frelich said the dramatic invasion of red maple, oak, and basswood into the region has already prompted him to reconsider the classification of the forest in much of the North Country. “I’m not even sure I would classify much of the area as boreal forest anymore,” he said. “There’s only little patches I would still call boreal.”

With as much as a third of the species diversity in Minnesota traditionally found within the boreal forests of northeastern Minnesota, Frelich said the loss of species diversity in Minnesota could be dramatic as the warming continues. Wildlife researchers believe that’s already contributing, at least in part, to the decline of iconic boreal forest species, such as moose, along with an influx of temperate forest species, like raccoons and wild turkeys.

Frelich said traditional boreal forest trees, like spruce, balsam fir, and jack pine are uniquely adapted to a short growing season, which has helped them to dominate the forests of northeastern Minnesota and much of central and northern Canada for millennia. As growing seasons lengthen, he said, it gives more southerly tree species, like red and sugar maple and basswood, an advantage. Frelich said the spread of red maple, in particular, has been dramatic in recent years, a fact that is most noticeable in the fall, when the reds and oranges of the maple, which had been rare in the region’s fall color palette, have become increasingly dominant.

Given the pace of the change, Frelich suspects the proliferation of maple may be a temporary phenomenon. “The maple may just be a phase in the transition to oak savannah,” he said.