Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

Ojibwe expert mesmerizes with history of timber on the Range

VIRGINIA- This summer’s Northern Lights Music Festival in Virginia featured a successful wrinkle from last year’s festival that’s surely not duplicated in any other similar music …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

Ojibwe expert mesmerizes with history of timber on the Range

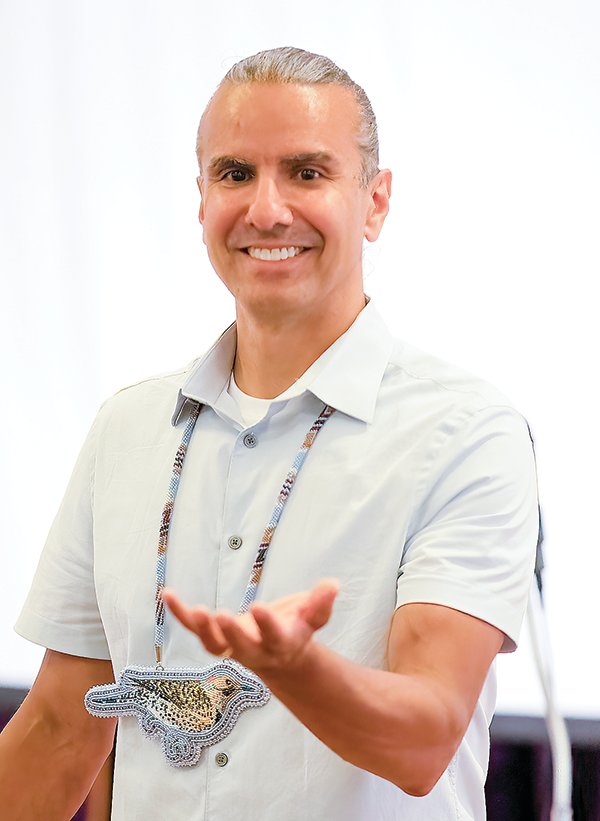

VIRGINIA- This summer’s Northern Lights Music Festival in Virginia featured a successful wrinkle from last year’s festival that’s surely not duplicated in any other similar music event— a lecture series on Iron Range history. However, it seems to be a perfect match for the talents of Bemidji State University professor and noted Ojibwe scholar Dr. Anton Treuer, who delivered a virtuoso performance of “Native Americans and Logging the Northwoods: An Indigenous History” on July 18 at the B’nai Abraham Cultural Center.

However, it seems to be a perfect match for the talents of Bemidji State University professor and noted Ojibwe scholar Dr. Anton Treuer, who delivered a virtuoso performance of “Native Americans and Logging the Northwoods: An Indigenous History” on July 18 at the B’nai Abraham Cultural Center.

Treuer is one of those rare presenters of history who seemingly inhabits past, present, and future almost simultaneously, moving effortlessly across the centuries from the Ice Age to his own hopes for a better future, deftly connecting the dots along the way about how the past informs our understanding of the present.

Treuer draws his information from an increasingly diverse number of fields that once were largely separate from history but are now integral to it.

“We now have disciplines that we thought would have nothing to say about things like who got here, when, and how that are contributing all kinds of information,” he said. “Genomic mapping has just yielded all kinds of information about what humans ate, how it affected their bodies, the movement of peoples, how they’ve been disconnected from one another. Anything you have read that’s ten years old or older is way off today. And that would include stuff that I was writing back in the day.”

Treuer began his lecture talking about the geological and ecological changes over time in northern Minnesota, and how the Ojibwe people who migrated here adapted to the environmental changes and available resources.

“As the topography shifted, people had to change their cultures,” Treuer said. “And as new technologies or understandings emerged, or even ways to structure societies, then people started to change and adapt.”

The introduction of Europeans to the Americas put into play a dramatic shift in the lives of indigenous people, and that was surely the case when they came to take the land inhabited by the Ojibwe.

“When they came to northeastern Minnesota, they looked at the big stands of virgin pine forest and they thought, ‘Wow, look at all the money that grows in the trees,” Treuer said. “By the time you get into the logging you’ve got a huge shift going on in human populations and economic conditions in America that changed everything here, and it would happen very, very quickly. The very first Ojibwe land cession in Minnesota doesn’t happen until 1837, and that’s not so long ago.”

While the Ojibwe ceded more land to the U.S. government in 1854 and 1866, their understanding of the transactions was quite different from that of simply handing it over to someone else.

“The initial treaties like the 1854 Treaty have very clear language. Native people are saying, ‘Hey, we’re willing to change the status of some of our land to shared use. But we are not extinguishing our right to use any of our land. And, so, all these clauses in the treaties that say that natives retain the right to hunt, fish, gather the wild rice, clearly the Native people were saying, ‘We can just stay here and we need to do life how we’ve been doing it.’ So even framing it as the Native sold the land is not quite accurate. Native people understood there would be a shared use, not an extinguishment of their rights.”

The post-Civil War era brought more huge shifts in land rights as homesteading accelerated and the government established an allotment policy to trim the 155 million acres of Native land inside reservations to only 50 million acres, opening up the rest to wider settlement. In northeastern Minnesota, that gave the growing timber industry access to more forest to harvest.

“All of that was ongoing in the very late 1800s and early 1900s,” Treuer said. “The timber boom was crazy. At one point, nine of the ten largest timber mills in the world were in Minnesota. It was a huge business and it fundamentally and permanently altered the landscape in many different ways.”

Losing the ability to harvest anywhere in Minnesota created hard times for Native people, and many across the Iron Range turned to the timber industry for help.

“If you could get a job as a logger, that was a way that made it possible to make ends meet,” Treuer said. “It was part of adapting to their new circumstances and economy, so it wasn’t all negative, but it was also complicated.”

For example, timber produced by Minnesota mills was used to build Indian boarding schools designed for the purpose of eradicating Native culture.

“Timber sales are being used to assimilate your children, while some of that money still transferred into other kinds of activities that would benefit tribal members,” Treuer noted.

With each dose of timber-related history, attendees also got a related sidebar from Treuer about a diverse number of topics ranging from the intricate sophistication of Native cultures that have been largely dismissed by Western culture to the need for society to find ways to pursue restorative justice. Each time he brought people back in some way to the topic at hand, in its own way Treuer’s verbal representation of a sacred circle and the completion of another phrase in his symphony of knowledge.