Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

Bird study raises alarms, and many more questions

There’s reason to be concerned about the results of the recent study that appeared in the journal Science that estimated a massive decline in bird populations in North America over the past five …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

Bird study raises alarms, and many more questions

There’s reason to be concerned about the results of the recent study that appeared in the journal Science that estimated a massive decline in bird populations in North America over the past five decades.

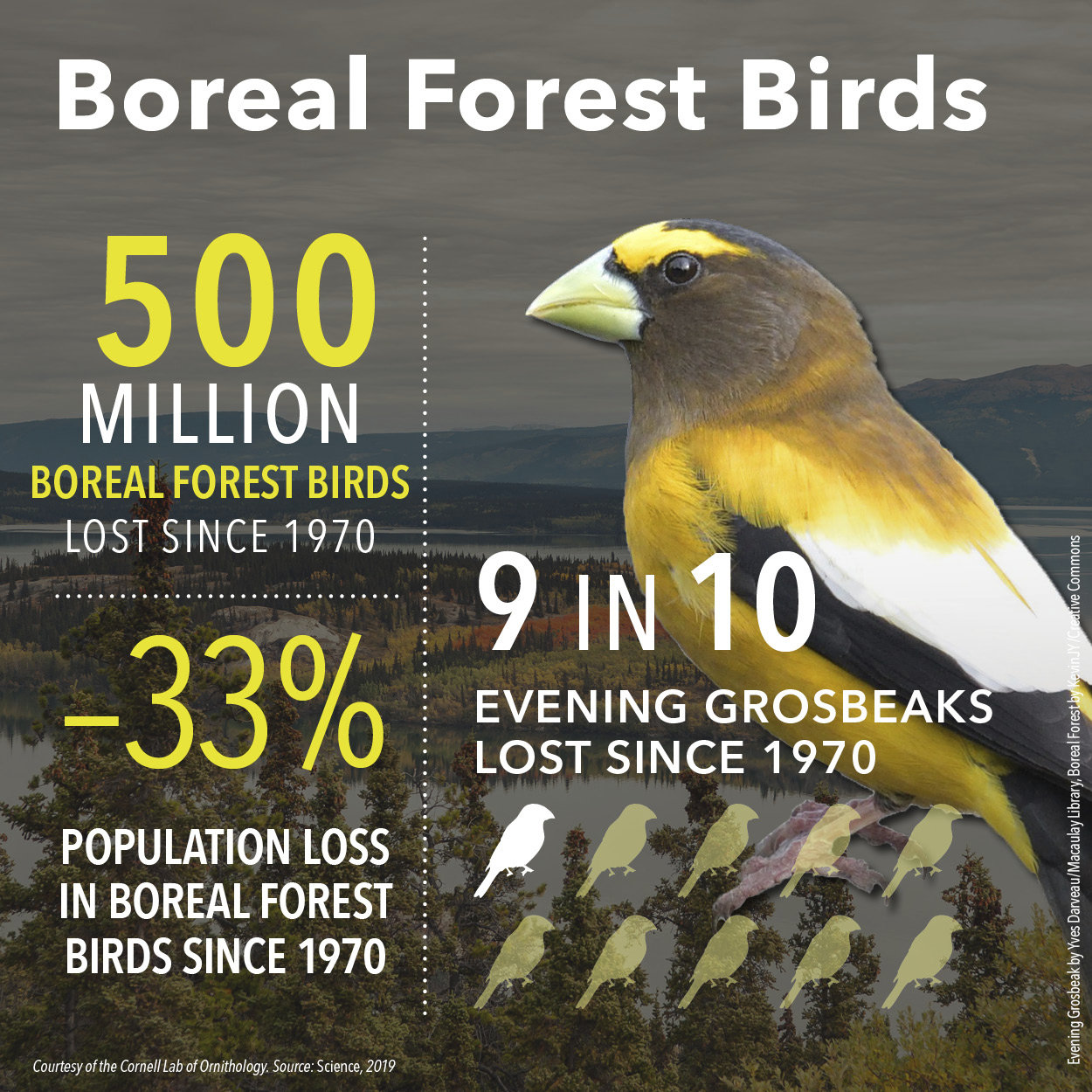

The top-line number, a loss of nearly three billion (yes, billion) birds was dramatic and it understandably received significant media coverage. While the study was inherently an estimate of something that can be difficult to estimate, the rationale behind the results are reasonable. The fact that the trend has been confirmed by many other data sets, from breeding bird surveys to Christmas bird counts, adds more heft to the argument that at least some birds are disappearing at frightening rates.

Coming on the heels of research suggesting a more-than 50-percent decline in insect populations, fears that our planet could be reaching some kind of ecological tipping point are certainly justified, even if not yet fully supported by available research. Taken together, these two major studies help to sound the alarm that much more research into the risks of ecological collapse is warranted.

While the dramatic numbers outlined in the recent bird study, led by Kenneth Rosenberg of the Cornell Ornithology Lab, justifiably caught the public’s attention, the details of the study, as usual, provide substantially more context and suggest that some of the more breathless headlines may have suggested an imminent crisis that the data does not yet support.

A few examples might help illustrate what I mean. First, there’s actually some good news from the study in that it found that the population of resident native birds in North America actually increased, by about 26 million. Most of that came from gains in the populations of waterfowl, which increased by an estimated 35 million, and the number of raptors, which jumped by 15 million. This suggests most other native resident birds, taken together, declined but only very modestly.

A couple observations are worthwhile here. First, both waterfowl and raptors have benefitted from conservation efforts over the past 50 years. Such gains show that changes in law, preservation and enhancement of habitat, and phaseouts of harmful chemicals like DDT, can make a tremendous difference.

We also have to recognize that the study’s baseline of 1970 hardly provides a snapshot of how bird numbers today compare to those before European settlement of North America. Barn swallow numbers have dropped about 40 percent over the last 50 years, a period that also saw the number of barns on the landscape fall even more dramatically. Were barn swallow numbers in 1970 artificially elevated due to the construction of ideal nesting habitat across so much of the rural landscape? Were the numbers of many bird species unusually elevated in the 1970s because humans had so dramatically reduced raptor populations? As I wrote here just last week, many of those raptors prey heavily on other birds. If each of those 15 million additional raptors eats 100 birds a year, for example, that equals 1.5 billion fewer birds. Do the math.

I don’t mean to suggest that increasing numbers of raptors are solely to blame for the decline in overall bird populations. But it would be scientifically unsupportable to claim that this isn’t a factor, possibly a significant one, in the decline of at least some bird species. In nature, after all, everything is connected. You can’t substantially increase the number of predators without affecting prey populations.

My point here is that we really don’t know how populations of many birds in 1970 compared to what was here originally. It’s possible, indeed likely, that some species benefitted significantly from the decline of raptors and now their populations are falling as a result of the return of raptors to the skies.

The dramatic decline of some grassland species, such as the western meadowlark, could be an example. As a kid growing up on the oak savannah in Bloomington, the fluid notes of the western meadowlark were an ever-present part of my summer soundtrack, yet they seem to have largely vanished from such habitats these days. But these are robin-sized birds that inhabit open country, with males that sing frequently, often from exposed locations. The return of predators from the sky has almost certainly had a significant impact on their abundance.

I suspect raptors have also played a role in the decline of house sparrows and starlings, two introduced species to North America which, combined, account for about 15 percent of the overall decline in bird numbers. Few bird enthusiasts will mourn the decline of either of these species.

Then, again, raptors probably have played a lesser role in the jaw-dropping decline of evening grosbeaks, which were once a bright and boisterous addition to most area bird feeders. This species has declined by approximately 90 percent since 1970, and it really isn’t clear why. No other northern finch species has experienced anywhere near this level of decline.

All of this stated, there is much in this study to prompt real concern. First, habitat loss is a serious issue. Those fields that held the meadowlarks of my youth are now housing developments and commercial centers. As habitats disappear, so do birds of all kinds and other types of wildlife.

The other big take-away from the recent study was that the decline in bird numbers has come almost entirely from migratory birds— and this is a trend that most birders in our region have certainly detected. Twenty-five years ago, the dawn chorus of warblers, thrushes, sparrows, and vireos used to create a cacophony during the height of the breeding season here in the North Country. These days, it’s more likely a solo performance than a chorus.

Given that the bird decline is almost entirely limited to migrants suggests that the losses are either occurring during migration, or as a result of losses while on their winter range. Habitat losses from the southern United States through Mexico to Central and South America are almost certainly playing a role. We know that the tropical forests in South America have been under tremendous pressure in recent decades and that is very likely contributing to the loss of birds and, unfortunately, it’s a loss over which we have very little control. Migration also poses many more risks for birds. Every tower, every new building with windows, every house cat allowed to roam untethered outside, is contributing to bird deaths during migration. Throw in climate change, which is affecting the timing and availability of food sources for birds and altering habitat in the process, and there’s little wonder that declines are being documented in so many species.

And it has to be noted that this study is just one more piece of evidence of the degree to which human activity is affecting so much of the natural world. Many scientists fear we’re in the opening stages of a biodiversity collapse that could utterly reshape the nature of our planet within a matter of decades. The reserachers also make note of the fact that the loss of biodiversity is not just about the loss of individual species— what this study demonstrates most strongly is the degree to which the numbers of once-common birds are declining. Few of them may be at risk of extinction, but their decline has real effects on the ecosystems they inhabit.

Studies like this don’t provide all the answers, but they do serve as a launching pad for much additional research aimed at answering the plethora of questions this study raises. It also, perhaps most importantly, provides a much-needed wake-up call for humanity. If it, even for a news cycle or two, gets us to consider our impact on our one and only planet, it serves a critical function. Hopefully, the right people are listening.