Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

A plan was approved a century ago...the BWCAW was the result

Arthur Carhart was dispatched to chart a recreation plan for the Superior

REGIONAL— A recreation plan issued just over a century ago by a then little-known landscape architect working at the time for the U.S. Forest Service, laid the groundwork for a revolutionary …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

A plan was approved a century ago...the BWCAW was the result

Arthur Carhart was dispatched to chart a recreation plan for the Superior

REGIONAL— A recreation plan issued just over a century ago by a then little-known landscape architect working at the time for the U.S. Forest Service, laid the groundwork for a revolutionary idea that reshaped a large swath of northeastern Minnesota.

In 1919, Arthur Carhart, of Iowa, was commissioned to develop a recreational plan for the recently-created Superior National Forest. It was the dawn of the automobile age and those who sent Carhart off into the forest were expecting a plan that would include the construction of roads to provide recreational access to the region’s countless lakes. Indeed, at the time, a proposal for construction of a road from Ely to the Gunflint Trail was gaining momentum.

But after two three-week-long canoe trips through the heart of what is now the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, the first in 1919 and the second in 1921, Carhart came back with a much different idea. His plan, issued in May 1922, proposed not roads, but the establishment of a large permanently protected roadless area that would continue to be accessed by canoe for generations to come.

“Why can’t the lakes become the roads?” Carhart asked. In his plan, Carhart noted with remarkable accuracy that the Superior “as a canoe country, would have few, if any competitors.”

That plan, after several months of review, was approved by Regional Forester A.S. Peck 100 years ago last month, marking the first of many steps forward in the official protection of the Boundary Waters. Less than four years later, U.S. Forest Service Chief William Jardine signed a plan to protect the Boundary Waters as one of the largest roadless areas in the country.

Carhart developed his plan at a propitious time in the history of the United States and the U.S. Forest Service. By the 1910s, the American frontier was largely gone and with it came a sense that the country’s once vast and spirit-defining wilderness was disappearing with it. Outspoken conservationists like Aldo Leopold, John Muir, Theodore Roosevelt, and others had begun to make the case for preservation of remaining wilderness areas of exceptional quality, and Carhart’s well-timed report spoke to that desire.

In his plan, Carhart described how the Superior’s unique landscape framed his approach. “Perhaps one of the biggest factors affecting a recreation plan for the Superior Forest lies in the wilderness conditions found practically throughout the forest,” Carhart wrote. “There is so little wilderness left where natural conditions are supreme that the Superior stands somewhat by itself in this type. The only other similar sections of land which can be reached by people of the United States are in Canada, or in the extreme upper corner of the state of Maine.”

Carhart spoke, as well, to the unique characteristics of the region and the benefits of retaining it in as close to a natural state as possible. “A final statement to emphasize the need of care in development of this forest seems hardly necessary but it is imperative that in the further planning of the recreational features of the Superior, it constantly be kept in mind that this is the only lake type play area owned by the United States and that the typical development as outlined here will enhance that feature,” Carhart wrote. “Further, that development imposing mechanical features, such as roads, too highly organized camps, urban types of hotels, et cetera, will not produce the greatest good for the Superior,” he added.

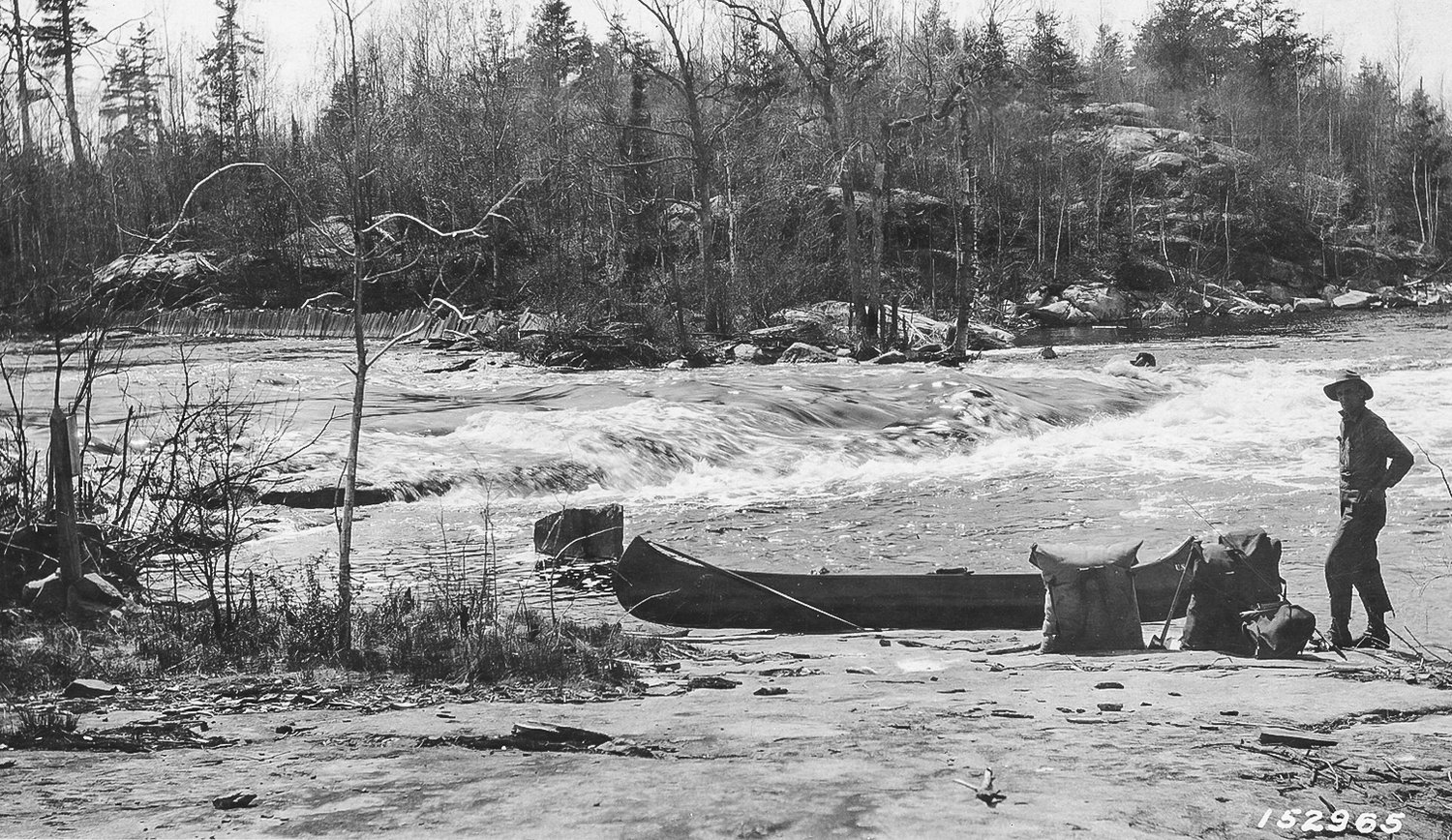

Carhart’s first trip took place just ten years after the creation of the Superior National Forest at a time when the Forest Service was still trying to determine how the vast region would be managed. “From the perspective of land use history, Carhart’s visit occurred at a key stage,” notes Lee Johnson, forest archeologist on the Superior. Logging had already occurred in large swaths of the Superior and pressures to further develop the area were building. Photographs taken by Carhart during his trip show the bare land left behind by logging operations and the visual impact of the timber cutting prompted Carhart to recommend, as well, that strips of uncut timber be left around the shorelines of lakes in the region. That recommendation took on the force of federal law eight years later with the passage of the Shipstead-Nolan Act, a law that has protected remnants of old growth pine and other trees along countless lakes in and around the Superior National Forest.

Carhart began working for the Forest Service in 1919 and the was the first landscape architect ever hired by the agency. He was first dispatched to Trapper’s Lake on the White River National Forest in Colorado to survey a new road and lakeshore lots. Instead, Carhart recommended the lake be protected from such development and, today, the 302-acre lake lies entirely within the Flat Tops Wilderness Area.

Carhart worked for the Forest Service for just five years, leaving in 1923 to pursue a career as a city planner in the private sector. Yet Carhart continued to advocate for wilderness and its value to the human spirit in books and other writings right up until his death in 1978. While no one person can lay claim as the founder of the concept of “wilderness,” Carhart has been referred to as “the chief cook in the kitchen during the critical first years.”